Every September, the world marks Sickle Cell Awareness Month, a time to spotlight a condition that silently affects millions yet remains surrounded by stigma and neglect.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 300,000 babies are born with sickle cell disease each year, with the majority in sub-Saharan Africa. In Kenya, the Ministry of Health estimates that around 14,000 children are born annually with the condition.

Data from Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital also shows that in the Lake Region alone, about 4,000 babies are born with the condition annually.

But, beyond these numbers are personal stories of endurance. For Brian and Teresa, sickle cell disease is not just a diagnosis, it is a lifelong journey of resilience, pain, and hope.

Young and Unbroken: Brian’s Fight With Sickle Cell

Brian Kedogo, a 22 year old sickle cell warrior, was diagnosed at the age of nine. Since then, his life changed and he had to adapt to a challenging life of frequent health struggles and learning how to cope with the condition.

“I was born in 2003. My journey as a sickle cell warrior began at Kenyatta National Hospital. It has been a rough experience but I keep trying to cope. When my parents first explained the condition to me, I was totally confused and overwhelmed not knowing how to go about it,” says Brian.

His journey has not been easy. He has faced stigma from peers and society, with many distancing themselves, believing it’s transmittable. Others avoid him because he is frequently in the hospital.

“Stigmatization is everywhere. People don’t associate with me because of my condition. Some think that they can also get infected,” he adds.

Growing up, stigma and lack of awareness were his greatest challenge. However, with time, he has learned to better understand and manage his condition.

When painful episodes occur, Brian manages them with painkillers, though not always effective. When the medication fails, he is forced to seek hospital care.

“I often take painkillers in times of painful crisis. Sometimes they don’t work, and I have to go to Kenyatta National Hospital, since nearby facilities usually can’t help,” explains Brian.

Even at the hospital, challenges still persist. Accessing specialized medication like hydroxyurea is another hurdle, as it is expensive and often unavailable. Financial constraints sometimes force him to skip hospital visits, worsening his health.

“You can go there with pain, but they tell you to wait in line. For hydroxyurea, sometimes you find it, sometimes you don’t. I’ve missed appointments because of financial issues,” he shares.

Sickle cell also caused additional complications. His hip has been damaged and he recently underwent a cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal). He notes that crises are usually unpredictable and the location of the pain often varies with age.

“It damaged my hip. Last month my gall bladder was removed,” he says. “The crises are tricky. During the day, you may feel fine, but at night the pain is very high, especially around midnight. The pain will then go slow at around 4 to 5 am. For me, it affects both hips, though when I was younger it affected my knee and ankles.”

Brian’s strongest pillars of support are his parents and the Joanne Chazima Sickle Cell Foundation. Friends rarely support him due to the fear of contracting the disease, yet it is a non-communicable disease, inherited from both parents.

“My parents are the only ones who have been with me ever since diagnosis. I also have one support group that has really helped. But friends and relatives haven’t been there much,” Brian notes.

Despite the hardship, he encourages fellow young warriors to keep fighting.

“To my fellow young sickle cell warriors, keep pushing. Don’t give up. Fight it until you make it. We have dreams and we must make our parents proud,” he urges.

He appeals to the government to recognize sickle cell warriors and provide consistent medical support, including the availability and affordability of critical drugs like hydroxyurea. He also calls for public awareness to end stigma.

“My biggest wish is for the government to help us access treatment and medication like hydroxyurea and to establish a nearby clinic for emergencies. The public should also be aware that sickle cell is genetic, not contagious,” he emphasizes.

September being Sickle Cell Awareness Month, Brian declares himself a champion in an ongoing battle. He hopes for better days while holding on to his determination to achieve his goals.

“I’m a champion! I must achieve my goals even though the crises overwhelm me. We, sickle cell warriors, are still strong. We can make it!” he adds.

Four Decades of Resilience: Teresa’s Journey

Teresa Adhiambo, a 41 year old sickle cell warrior, was diagnosed at the age of one. She became aware of her condition around the age of six. During her primary school years, she was often excluded from sports and physical activities without clear explanation, leaving her feeling isolated and confused.

Unlike her peers, she experienced delayed physical development, which became more evident during adolescence. She began her menstrual cycle at 23.

“I battle sickle cell every day. My journey began in the 1980s, but I only became more aware about it in primary school. They kept excluding me from sports without telling me why. In high school, I realized that I was different. Everyone else was growing normally, but I faced delays,” says Teresa.

Exclusion has extended into adulthood, with Teresa often left out of hikes, church outings, or sports days. To cope, she focuses on less physically demanding hobbies, such as learning instruments, which she notes lean toward introverted activities.

“Since I can’t do much even if I participate in those physical and social activities, I often try to find something else that is not physically demanding,” she explains.

As a fashion designer, Teresa manages her workload carefully, taking only what she can handle during busy seasons and ensuring she rests adequately during weekends to recover from physical strain.

She always keeps painkillers near her, using them to manage painful episodes, often triggered by travelling.

“At work, I pace myself. If the season is fast, I take less work. If it’s slow, it’s manageable. As an adult, crises occur about once every four months, especially after traveling,” she says.

Before she had health insurance, accessing treatment was extremely difficult. At public hospitals, she sometimes waited up to nine hours in the emergency room before being attended to, even in severe pain.

With insurance, she can now access care more easily. Teresa also suggests that clinics, especially in rural areas, should be equipped to handle sickle cell crises.

“People living with sickle cell need urgent action so that their organs don’t shut down. Every nearby clinic should know how to deal with it and be able to at least save lives. There should also be a standardized guide on treatment,” she stresses.

Family support has been her greatest strength. Friends have been a mixed experience, some have walked away, especially in dating, while others stayed.

“My family has been very supportive. I have not walked the journey alone. Friends have been different; some left, especially in dating, but at least it showed me who could stay,” she says.

Teresa emphasizes that sickle cell is not contagious and urges people to get tested and know their genotype before having children.

“It’s important to know your genotype so you can make informed choices when planning a family. Let’s end the stigma, sickle cell is not contagious. We are normal people and can live fulfilling lives. I’m 41 and living fully. We can manage it,” she encourages.

Understanding Sickle Cell: From Detection to Common Misconceptions

According to Selina Olwanda, Executive Director at Children Sickle Cell Foundation, red blood cells normally lives for about 120 days, but in people with sickle cell disease, they only survive for 10 to 20 days. She explains that the disease is inherited when a child receives abnormal genes from both parents.

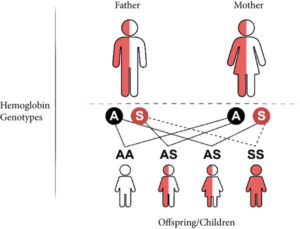

“Sickle cell disease is a genetic disorder inherited from both parents, and it affects red blood cells. Sickle cells irritate blood vessels and reduce oxygen flow, which can cause severe complications. If both parents are carriers (AS + AS), the chances are 25% of having a child with sickle cell (SS), 25% of a normal child (AA), and 50% of a carrier (AS),” she explains.

Selina underscores that infants may not show symptoms for the first six months because they rely on maternal blood, but as the child begins producing their own red blood cells, symptoms emerge.

“During the first six months, a child may look healthy, but once their body starts producing red cells, signs such as painful swelling of hands and feet, yellow eyes (jaundice), nonstop crying, and paleness may appear. Parents should seek medical care immediately for a hemoglobin electrophoresis test to confirm sickle cell disease,” she advises.

Early detection improves quality of life, but still many families face challenges. Diagnosis has been inaccessible and expensive for many decades, leading to late diagnosis after complications develop.

“Until recently, diagnosis was unaffordable for many. Imagine being charged between 5,000 and 10,000 shillings, especially for families struggling financially can hardly manage that. As a result, many people are diagnosed late, often after developing complications,” Selina says.

Sickle cell is a lifelong, chronic illness. Bone marrow transplant is considered a potential cure, but still remains out of reach for many African patients.

“Unfortunately, in Africa we don’t yet have institutions offering bone marrow transplants for sickle cell. The treatment requires a matching donor and huge financial resources. In Kenya, management is the focus, early detection, proper medication, regular check-ups, and support groups are critical,” she explains.

She highlights that children with sickle cell often require referrals for pain, infections, anemia, and organ complications. Misconceptions surrounding the disease fuels stigma, discouraging families from seeking timely care.

“Stigma due to misconceptions has prevented many patients from seeking the right medical help,”she says.

Selina further emphasizes that awareness should begin at the household level before expanding to communities. Having nearby primary health facilities reduces long distance travelling.

“Awareness must start with family members, then extend to communities. The government should invest heavily on awareness campaigns, through billboards, radio, TV, and community programs. Also, having a nearby clinic is crucial because frequent hospital visits are costly and exhausting for patients,” she emphasizes.

Selina calls for stronger infrastructure, more funding, and a national registry of sickle cell patients to improve treatment and planning.

“We need more funding, focus, and awareness for sickle cell disease. A national registry would help us map out where patients live, which facilities serve them, and how they respond to treatment,” she says.

Although sickle cell has long been neglected, she acknowledges recent progress with the establishment of the Social Health Authority (SHA), which offers a new pathway for funding.

“It is unfortunate that we’ve lost so many lives because there was no dedicated national health funding. Today, SHA is creating opportunities to fund sickle cell, but it’s still a work in progress and we need to push for it to totally work and save lives,” notes Selina.

Finally, she urges investment in local drug manufacturing to reduce the cost of treatment and strengthen care systems.

“Some of these drugs are very expensive because we import them. If we build proper infrastructure, patients won’t need to travel from one county to another to find help. For this to happen, the government, policymakers, doctors, communities, and all stakeholders must work together,” she concludes.

Brian and Teresa’s story is both a personal testimony of endurance and a call to action for greater societal understanding and government intervention to improve the lives of people living with sickle cell disease in Kenya.