West Africa is facing an escalating textile pollution problem, fuelled largely by the global second-hand clothing trade. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the OR Foundation, tens of thousands of tonnes of used clothing arrive weekly at ports across the region, with a significant share landing in Ghana. Much of it is low-grade waste that cannot be resold or reused. Up to 40 percent ends up as environmental waste, burned in open fields, dumped in waterways, or buried in informal landfills.

In Ghana, this issue is especially visible in markets like Kantamanto in Accra, where traders receive up to 15 million garments every week. Estimates from the Accra Metropolitan Assembly show that about 100 tonnes of textile waste are generated daily, and much of it is unaccounted for in the country’s formal waste management systems. The result is visible across urban and coastal spaces. Blocked drains, toxic smoke from burning synthetic fabrics, and mounting piles of dumped clothing in wetlands and communities are now common.

Within this broader crisis, a young Ghanaian graduate student is attempting a different approach. Papa Yaw Amankwah, based in Tarkoradi and currently pursuing his master’s degree in Art Education at the University of Education, Winneba, is using worn-out denim to create fashion items under an initiative he calls Jeans Nkoaa, translated as “Only Jeans.” Without institutional backing, a team, or access to industrial machinery, he repurposes discarded jeans into custom neckties, trousers, bags, and footwear. His work offers both a creative alternative to waste and a model for sustainable reuse.

The project began after his own experience working in the second-hand clothing sector. Frequent visits to Kantamanto exposed him to the sheer volume of clothing that never makes it to the market stalls. Bales are opened, garments are sorted, and what is deemed unsellable is immediately discarded.

At landfill sites, he witnessed piles of synthetic clothing releasing smoke and chemicals into the air and soil. It was this pattern that made him reconsider his role in the cycle.

“I used to sell thrift,” he said during an interview. “But when I saw how much of it just goes to waste, I started thinking differently. I felt there was something I could do about it. Maybe not everything, but something small that still matters.”

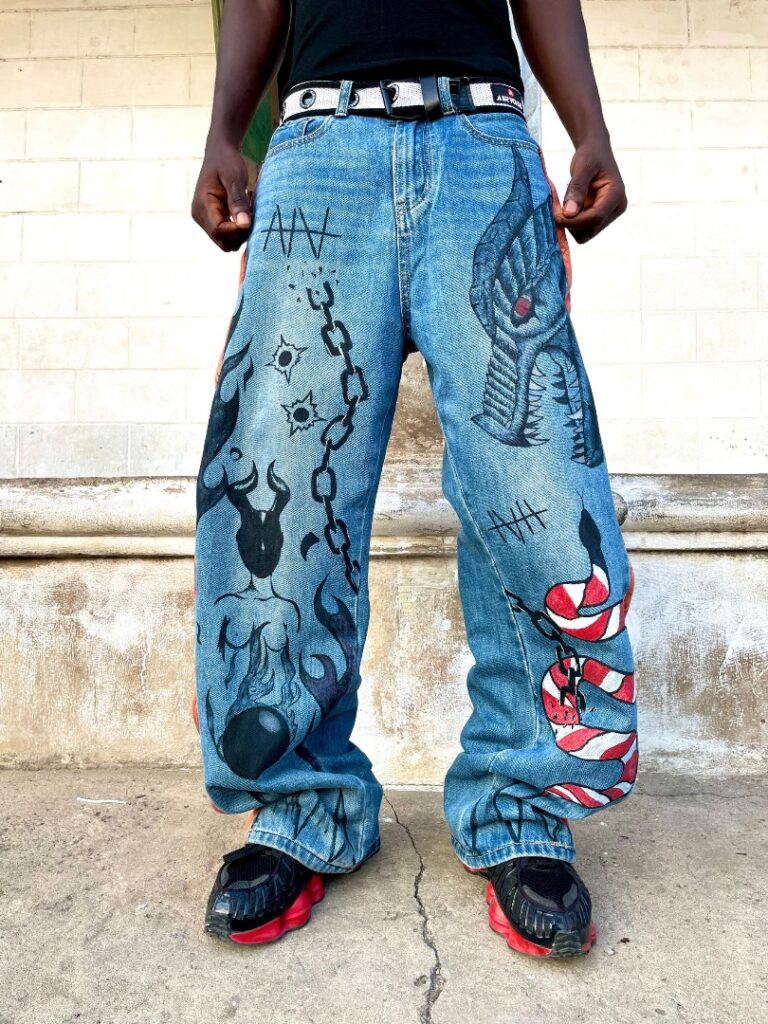

Photo courtesy// Papa Yaw Amankwah

He started collecting discarded jeans, one of the most durable but environmentally problematic fabrics. Denim is thick, chemically treated, and slow to decompose. For Amankwah, that durability became an opportunity. Instead of seeing waste, he began seeing raw material.

He sources the denim from Kantamanto and other markets, paying out-of-pocket for clothes others see no value in. Back at his residence, he washes the fabric thoroughly before working on design concepts. Without a dedicated workspace or his own equipment, he relies on machines borrowed from colleagues in the university’s fashion department.

These machines are not designed for heavy fabrics like denim and frequently break down. The technical limitations slow his work but have not stopped him.

Currently, he works alone. Every stitch, cut, and concept comes from his hands. There are no assistants, no partners, and no production line. The initiative is funded entirely from his personal resources, including small income from product sales.

Photo courtesy: Papa Yaw Amankwah

Despite the challenges, Jeans Nkoaa is growing into more than a clothing brand. It is a form of advocacy. At craft fairs, exhibitions, and in one-on-one sales, Amankwah uses each transaction as an opportunity to talk about Ghana’s waste burden and what sustainable alternatives can look like.

“When people buy something, I tell them where the material came from and why I use it,” he said. “They leave not just with a product but with an idea. Something to think about.”

According to recent trade data published by Africa business insider, Ghana’s importation of second-hand clothes increased from 164 million dollars in 2022 to nearly 180 million dollars in 2024. Kenya’s imports surpassed 298 million dollars in 2023. The bulk of these clothes are shipped from the UK, EU, China, and the United States. While the trade supports many livelihoods, especially for small-scale retailers, the environmental impact is rarely accounted for in national waste strategies.

Papa Yaw believes the long-term solution lies in public education, youth involvement, and integration of sustainability into creative industries. After completing his master’s degree, he intends to teach at the tertiary level, where he hopes to formalise waste-focused upcycling within art and design education. The goal is not just to expand Jeans Nkoaa but to create systems through which other young people can engage with environmental issues creatively and practically.

Photo courtesy//Papa Yaw Amankwah

He also sees room for collaboration with local tailors. Many generate large amounts of fabric scraps that are either burned or discarded. By introducing basic upcycling techniques into tailoring and fashion production, he argues, it is possible to reduce that waste before it ever reaches landfill.

“I’ve seen people in other countries trying similar things,” he said. “Some do it just for money. But even then, they sometimes leave more waste behind. I want to do better. If we train people the right way, it becomes something that lasts.”

At the moment, Jeans Nkoaa continues as a one-man project with limited resources. But its impact, consistent and rooted in local knowledge, points to a path forward. While large-scale solutions to Ghana’s textile waste problem remain slow and underfunded, efforts like Amankwah’s offer a working example of what innovation from the ground up can look like.

He hopes for support from NGOs, sustainability-focused philanthropists, or educational institutions to scale up the project in other parts of the country