It is a regular working day at the Standard Media Group bureau in Nakuru City, Kenya. On the third floor of the building along Kenyatta Avenue, the sound of traffic and boda bodas echoes from the street below. Inside the newsroom, the only sounds are the tapping of keyboards as journalists work on their assignments.

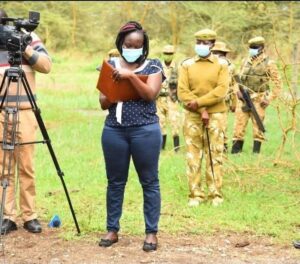

Caroline Chebet, a journalist known for her coverage of conservation and environmental issues, sits at her desk reviewing photo folders on her computer. She pauses at an image of the African Grey parrot, a species at the center of one of her major investigations. Her expression reflects the weight of the story behind the bird.

Chebet has reported on conservation, agriculture, climate change and wildlife for more than ten years. Her commitment to nature is evident in her journalism.

“I love nature and especially the wild. Anything that threatens it concerns me deeply. When I think about endangered species, I feel compelled to act,” she says.

In 2021, Chebet began investigating how the African Grey parrot was being trafficked from the Democratic Republic of Congo through Uganda into Kenya. The bird is listed under Appendix 1 of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, which means it faces extinction and should not be traded locally or internationally.

“I posed as a buyer and was surprised at how easy it was to arrange a sale. The seller was ready to deliver the bird as soon as I sent Ksh 25,000,” Chebet explains.

That interaction opened the door to a wider network of wildlife traffickers. Chebet soon uncovered links between smugglers operating across several African countries, supported by the ease of cross-border movement.

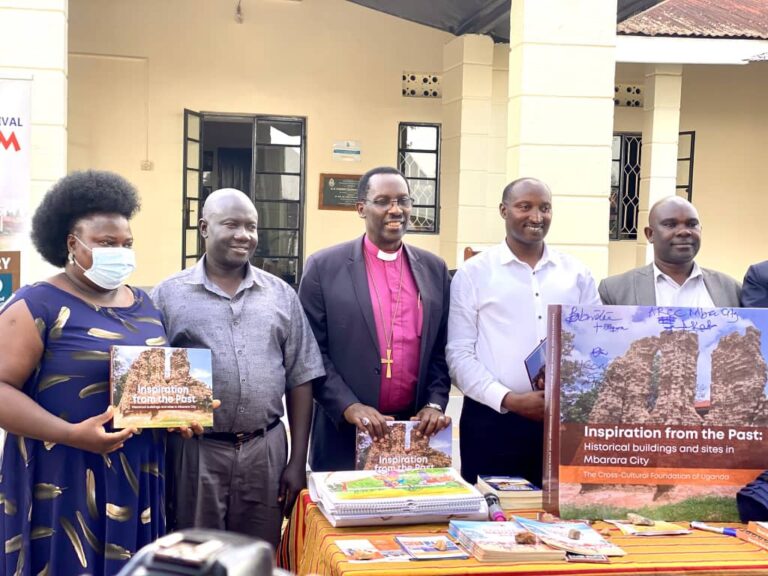

Erick Rotich, the Deputy Director of Immigration in Kenya’s South Rift region, says travel within East and Central Africa is relatively simple.

Erick Rotich, the Deputy Director of Immigration, South Rift Region, during the interview. (Photo/Courtesy: Hillary Fletcher)

“To move between countries like Kenya, Uganda and Burundi, a valid passport is enough. For Tanzania, South Sudan, Rwanda and the DRC, a temporary permit is required. It can be obtained online after paying Ksh 300,” says Rotich.

Chebet says this flexibility in movement helped her track wildlife trafficking routes and connect with local sources in different countries.

“It helps a lot to be able to travel easily across the region. It allows deeper investigations and access to key contacts on the ground,” she says.

The African Grey parrot is native to the rainforests of countries including Cameroon, Congo, Gabon, Ghana, Angola and parts of Kenya. It is targeted for its intelligence and ability to mimic human speech. In 2023, there were 930 African Grey parrots in Kenya, with only 12 found in the wild. The rest were in homes and tourist facilities.

According to a 2024 report by Nature Uganda, the country has more than 1,070 bird species, the highest bird species density per unit area in Africa. Uganda is considered a key transit route in the illegal trade.

Chebet’s original story, published in 2021, prompted the Kenya Wildlife Service to draft and publish a protection policy for the parrot. Her work was later recognised by the Earth Journalism Network in 2022. But a follow-up investigation in 2023 found that illegal trade had resumed despite the policy.

Chebet then made plans to travel again to Uganda and Congo to gather further evidence.

“Crimes like wildlife trafficking, corruption and money laundering go beyond borders. They cannot be handled effectively by one country alone,” she says.

Her investigation was supported by organisations including World Animal Protection in Kenya and Uganda, Nature Kenya and the World Parrot Fund.

Free movement of people across African countries is a key goal of the African Union’s Agenda 2063. The AU’s protocol on the free movement of persons, the right of residence and the right of establishment aims to promote regional integration and cooperation.

Free movement also allows journalists from different countries to work together. They can investigate stories, train, and share ideas.

Dr Michael Ndonye, a media scholar and head of the Mass Communication Department at Kabarak University, says digital tools have reshaped how journalists work.

“Cross-border collaboration has improved because of technology. Journalists can now collect, process and share news more effectively using mobile and digital platforms,” says Dr Ndonye.

Chebet’s work shows that African journalists, including women, are at the forefront of cross-border investigations. Her efforts have contributed to greater awareness of wildlife trafficking and exposed weaknesses in enforcement and policy implementation.

From her newsroom desk in Nakuru to fieldwork in Congo and Uganda, her reporting has shown that cross-border journalism is not just possible but necessary. The ability to move freely across countries has enabled Chebet to follow the story and reveal the realities behind one of the world’s most trafficked bird species.

Watch Caroline Chebet’s full interview and learn more about her investigation here

This story is produced as part of the Move Africa project, commissioned by the African Union Commission and supported by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of GIZ, the African Union or the Africa Feature Network.